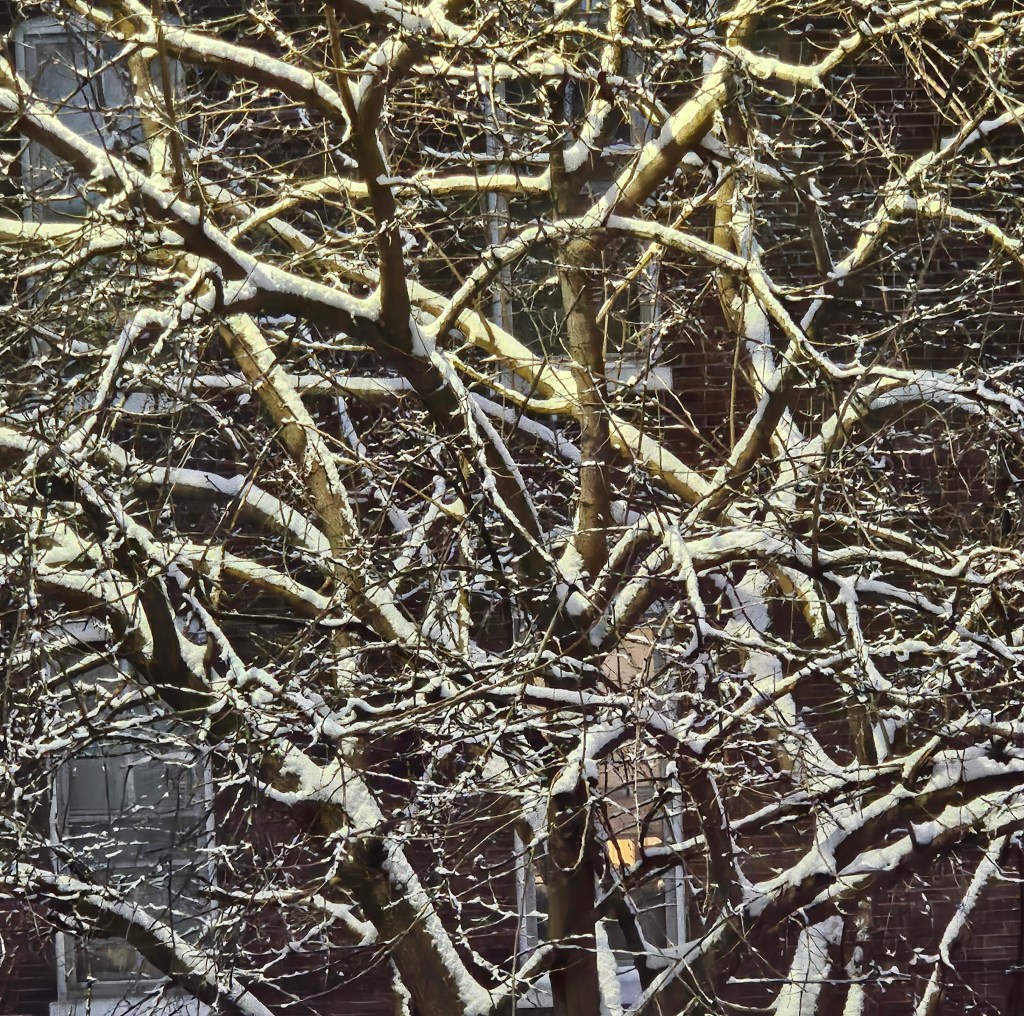

Photo credit: Ranney Campbell, 2025.

when my brother stomped the, that he made,

semiconscious

boy fresh stepped off

the bus lain face down

in the mud

blood puddle,

but something cracked.

Photo credit: Ranney Campbell, 2025.

Don’t you ever get lonely, he asked.

I understand, I don’t like people either

but sometimes, he said, I just need them.

Big toes tucked into the start of the crook of the croup

Into the dark dun stripe

Little toes flared back, pressed into hot slick coat

I’d brushed, curry first, then hard straw,

then smooth soft, then shine

Three hours, starting at daybreak

When he and I blew mist to the air

When he and I looked into each other

When he turned his head from the hitching rail

and I fell into that rich brown there

And he told me he knew how I cared for him

He told me he knew

And he didn’t lie

A horse won’t lie to you

My toes in the crook of the croup

In the stripe of his dun

Knees in low ribs

Collar bone on his withers

Breasts on each side, holding me centered

We’d been hours in

through the head-shaking, snorting, dancing gait

We’d settled and found a place

where grasses brushed mid-barrel

My cheek set between his shoulder and neck

He rocked a clomping rhythm

My body bent with his

bareback measure

That’s what I thought of

and I shook my head, no.

I don’t have casual relationships, I said,

I’d rather be alone.

Originally published by Shark Reef.

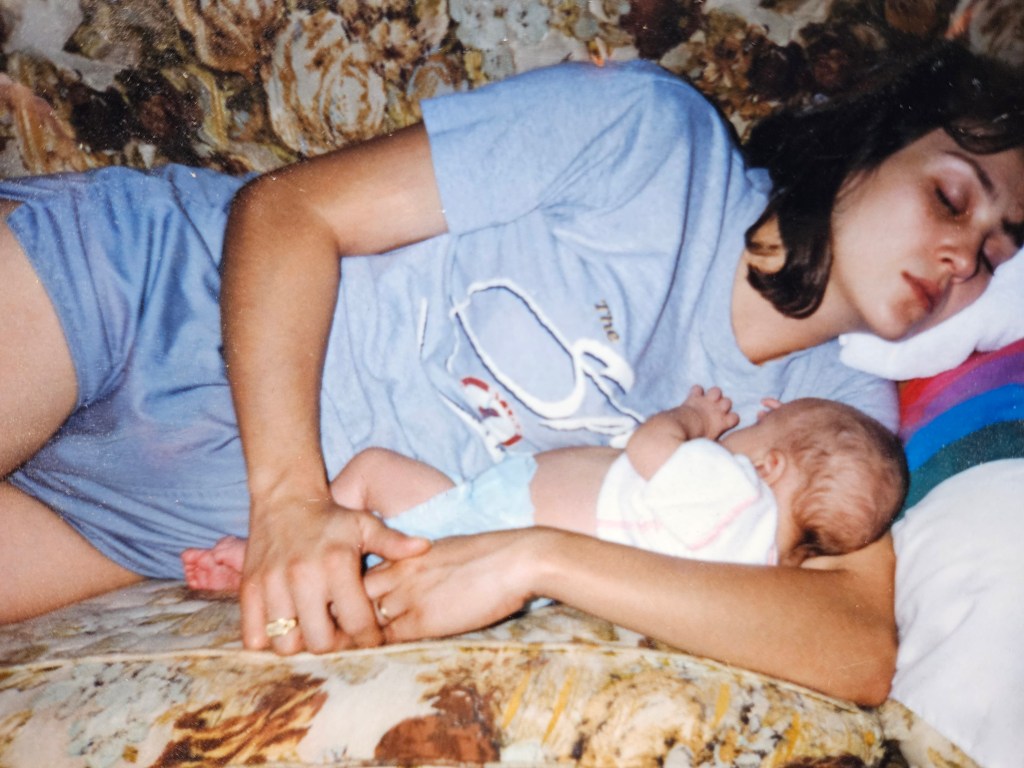

Photo: Pickles, three years old, still time to grow, Smiley Road, 1977.

You.

Woman.

You made the word a curse word.

I could never say it.

As a girl.

Woman.

It sounded dirty out of my mouth.

Woman.

Made my lips feel soft and round.

Woman.

Like womb.

Like pornography.

Spread open.

Never could say it without feeling nauseous.

Without my lips numbing feeling like slow motion.

Compromise.

You.

Woman.

With your side bends.

Your loud sharp dresses stiff.

Your desperation.

Woman.

Smelling like flowers.

From some garden we never been in.

Pink lipstick.

Yellow curlers.

Rouged cheeks.

Red phony rounded.

Coquettishness.

Painted chalkboard scraping fingernails.

Smiling wide dead.

Dulling eyes to seem stupid for them.

Using that voice that didn’t belong to you.

Sweet faltered quiet.

For men not my father.

The others.

You slut.

slut

i could always say that word

once my father said it

when you dragged me out of bed

in my long cotton nightgown

creamy white flowered dusting the floor

sat me rubbing my eyes

made me stay ’til midnight

with your face tight knotted

at the kitchen table to hear the drunken rant

to prove to me that he was not my hero

when he turned and told me

red-eyed and wobbling

i would grow up

to be a slut

just like my mother

before i knew what that word meant

Not like you.

Woman.

Grown.

Done.

It is dirty.

That word.

I make it.

I take it.

Back bending.

Vamping flattery.

Front bending.

Before them.

Assaulting red lips with heat.

Not a bought stick.

Buff shine.

Nails digging.

Low toned groaning.

Bare skinned.

Witted.

Loose haired.

Clothes on the floor.

Leave them.

Dazzled as they lay.

Lay them down.

Climb on them.

That will have me.

Take them in.

Me.

Originally published in Misfit Magazine.

Photo: 2023.

she could smell a cop uncanny

she could swing a bat without shame

she could feel a milligram difference on her middle finger

lids dropped chin lifted slight sway like trancing

circled men silent awaited the verdict

light or heavy

she could knock’em out, piston fist’em

keep her mouth shut hours or days

pout it and drop’em, slink blend the wallpaper

when the law busted loudmouth’s party on the cul-de-sac

slither out unseen

with somebody’s bottle of Jack off the kitchen table

since they’d be in jail anyway

cuss like a barge worker, laugh big, or never be made to

no matter what, when she wanted

verbal drop any professor

terrify a badger with a glance black squint

or purr sable

only would scoot under the bed

let them push boxes and towels around her

shallow breathe this custody

for the Outlaws

no others

and when the big men came

to the back house from out of town

and wouldn’t answer to the names they said theirs

up the volume

Or, whatever the fuck your real name is, Boss Man,

offer a cold beer from the fridge

firm arm curled out stretching supple

arch twisted brown tied halter painted jeans

and they snapped to

Originally published by Anti-Heroin Chic.

Photo credit: Beth Kimball, 1999.

my friends and cousin implored me to stay

at the bar when I twirled and told them, grinning,

I was leaving with three young men I’d just met.

next morning, when I drug back into the shack

I told the story of the mansion where I had landed,

such as the height of the ceilings and how many

bathrooms it had and of the host’s bragging

while serving liquor I had no appreciation for

and the endlessly seeming lines of cocaine

and exhaust of primo weed and the cobalt blue tile

of the kitchen counters and walls and the butcher

block isle below hanging every kind of copper

-bottomed pan and pot and of all the time

those boys spent on the phone futilitarian trying

to find prostitutes with no notice at three or four

in the morning and how disappointed they were

and how I allowed six hands all over me for six

crisp hundred-dollar bills and a sunny side up

and wheat toast breakfast with whipped butter

by sterling silver spreader

in air-conditioned sit down

and a forty-five-mile ride

home in the land rover after and when I looked up

at my cousin across coffee cups, she asked how

I always found the richest guys no matter what,

whatever room we would drop you in,

from hundreds

of men, you always pick them, every time,

how do you do it,

is it the shoes,

no anyone can buy shoes, I said,

but what then,

and all I could see were her fractured blue eyes

of our childhood,

it’s their eyes. there’s a comfort there.

it’s the comfort that attracts me.

it’s in their eyes.

she nodded so mildly

no one else must have noticed

but she and I knew

and we were back sitting on the bank

in scratchy grasses making sassafras tea,

with yellow sun baking our yellow and white

and ash and wheaten heads, fresh pulled and shook

in a bottle we found half full with mud

and washed out in the crystal creek

where there were no mothers

trading daughters to men in the dark

Originally published by Drunk Monkeys.

Photo credit: Plato Terentev.

Brightest lights. White walls. White floors. White sheets. White stiff cloth on people who bustled about. Blurring and clearing in and out of my vision. And silver shining. Silver rails at the sides of the table I was on. Silver instruments on silver trays with silver legs. White and silver glared and glistened harsh and it was so cold.

Pushing from inside, a want to get up and run. Out the sliding glass doors I saw occasionally open. But something impaired. I struggled to get up, but could not. I tried again and again and it took a few attempts before I realized it was not something physical holding me down, I was not stuck in some sort of jelly, as it felt, but was somehow mentally unable to function. I could not command my body. Panic rushed through me as it dawned, I had been drugged.

I knew I had to overcome the drugs I had been given by my strength of will. I knew my life depended on it. I knew that if I could not get out without being noticed that I would have to fight my way out. I began to get off the bed but was so clumsy about it I was noticed before I could get both feet on the floor. The one who noticed called for help as she rushed anxiously toward me and eased me back down. She was able to ease me down, because the mere effort of sitting up and getting one leg swung around the side of the table had exhausted me to the point that I could no longer sustain even the panic. My body shut down and I faded into unconsciousness.

There were times, moments, muffled or warbled voices. Other times shadows passed across my eyelids. Once, I recognized the blood pressure sleeve tightening on my upper arm and clearly heard the voices of the nurses. They spoke of the implausibility of my continuing survival.

“She still here?”

“Yeah. But she’ll never make it.”

In my head a thought came as a scream; I can hear you! But I couldn’t move. I tried desperately to communicate with them. I used all my might, all my concentration, to attempt to move a finger. Couldn’t. I planned. I plotted. I came up with the idea that the next time they came close, I would blow, puff, or somehow exhale to indicate my cognition.

The attempt failed. Doleful washed as their sounds faded. Then I realized that I hadn’t released the sigh that should have come naturally along with this deep discouragement. Then noticed, even the rhythm of my breathing was not in my control. Fear rushed. Tired me. I gave up the conflict and thought, as I drifted off, of the signature on my driver’s license to donate my organs and hoped I would not be so aware if that came to fruition.

I suppose over time my blood regenerated some, because all at once I sat straight up, easily flung my legs around, took a breath to summon my strength and hopped off the gurney. A small mob of nurses pushed me back down. I was still weak, but now angry. A hostile resolve to leave could not be restrained by three of them. This elicited the attention of a young doctor with curly brown hair.

He approached me directly.

“What’s your name?”

I was thrown. Thoughts spun like a disjointed carnival ride. My name? Well, of course. I know that. It’s … it’s … uhh … it’s … Name. Yes. I know this. Sue. Yes! That’s it!

“Sue!”

I almost shouted. I was beaming with the thrill of having come up with it. My name. Sue. Yes. I was quite confident about that.

This genteel man then became an inquisitor with a bothersome barrage of somewhat troubling questions.

“Sue what?”

“Huh?”

“What’s your last name, Sue?”

Stumped, I smiled coyly.

“You, sir, ask very difficult questions.”

He was unfazed.

“What year is it?”

I felt the surprised and puzzled expressions on my face before I recognized the feelings. I examined the feelings. The surprise was that I was puzzled. I was thinking, I should know this. There was a time when I knew this. Was it yesterday? I can’t remember yesterday.

I took a stab.

“1862.”

That seemed right.

By their faces I could tell, I was off by a century or so.

“1962?”

He shook his head.

“1964?”

“You’re getting closer, but let’s move on. What state are you in?”

Dumbstruck.

“Can you name a state?”

I could picture the outline of the United States, but I couldn’t name it. I searched my brain and imagined the shape and sought a name from within it. They waited. Watched me struggle. Finally, an answer came like an explosion.

“Dakota!”

This seemed somehow to appease the gathering of curious onlookers and they dispersed, leaving one nurse and the young doctor behind. He pronounced that I had amnesia. I thought, Gee, I don’t know my name and I could have called that one.

Over the course of a few hours, I had a variety of outbursts when I came to. Sometimes I was hell bent on escape from the apparent cult my boyfriend, who hovered on the edge of the scene, had sacrificed me to. Other times I had no idea who he was.

“No. I don’t know him.”

He looked so sad. I added, “Maybe he’s a friend of Ron’s.”

Then he looked angry.

“Who’s Ron?”

Sometimes I just wanted out. I was so near the doors. A few times I attempted to make for them.

The doctor came to me and asked why I was so insistent on leaving.

“I just want to.”

He was tickled.

“You don’t know who you are. Where do you intend to go?”

I lifted a finger pointed toward the doors, marginally wobbling.

“I don’t know, but from the looks of things, I’m in a jail or a hospital and either way, I want out.”

I wasn’t the only one disagreeable. A large, white-clad woman shook a chunky finger in my face while lecturing me on the consequences of drinking and driving. I grabbed her starchy shirt and threw her onto one of the nearby wheeled trays, bouncing a shattering sound off the walls as the instruments flew, while I growled, “I wasn’t driving.”

I jumped off the gurney and headed for the door.

Two steps and they had me back down.

This brought the doctor back. He squatted down a bit, leveled off with me, eye to eye, put one hand on each of my knees.

“Sue.”

He got my attention when he used my name, the only thing I knew.

“You have a serious head injury. We can’t let you leave.”

I lifted my hand to my forehead and touched my fingers to the gaping gash above my eye. I felt the odd sensation of the pressure of my fingertips on my sticky exposed skull. The skin hung unnaturally with loose edges in folds around my fingers.

“Oh, this?” I waved my hand out casually. “That’s nothing.”

Blood flew off the ends of my fingers through the air. It struck curious. I examined my hand. More blood. And all the way up my arm. My gaze fell to my shirt. Blood drenched. I raised my hand to my hair. It had become curly, as it did when wetted, and I felt the thick, gooey mess. This was all blood. A very large amount of blood. I nearly fainted in horror and dropped back heavily onto my elbows.

I sat back up and looked at him beseechingly. Our eyes met. Locked. Searched. He paused and leaned back, cradling his chin between the thumb and fingers of one hand, crossing the other over his chest and holding his elbow. After a moment this way, he looked at his watch.

“Well, you’ve made it eight hours. I guess we’ll sew that up.”

He called a nurse over and she found me cooperative, since now I reeled with the knowledge of the gravity of my injury, the amount of blood, my jeans caked with dried blood, soaked through to my thighs, the skin of my thighs stuck to the cloth with it. I was no longer bleeding and wondered if that wasn’t just because I had run out of blood. This made more sense of the weakness. And the head injury he reported explained the memory loss. I pondered these subjects dreamily until I felt a pain so sharp and piercing that it seemed to go straight through my brain and to the base of my skull.

“Sorry, I just need to get this piece.”

I tried to relax and be still and let her do her work. But, again, the pain was more than I could bear. “STOP,” I snarled as I grabbed her wrist and pushed it away. I leaned forward, unsteady, trying to keep vomit down, to remain conscious, and with a throttlehold on her arm.

The doctor, who knew my name and used it, appeared. The nurse pointed with her tool to a piece of glass she couldn’t get.

“See, this one, I can’t quite…”

When she began to prod again I didn’t at first recognize that the guttural cry I heard was coming from inside me.

“That’s her skull!” Then he groaned, “I’ll take it from here.”

I was so relieved to have him take it from there. He had stopped the overwhelming pain she had caused. He knew my name and used it. He was the man who had declared I would live. He introduced me, later, to my mother in such a way as to spare her the immediate knowledge of the depth of my amnesia.

“Here’s your mother, Sue.”

I followed his lead.

“Hi,” the sentence hung there as I tried to recall whether it was mother or ma or mom or mommy. She was too distracted by the rest to notice.

Over the next couple of days, the doctor and I enjoyed our time together, when he came in during his rounds. We bantered about our opposing views on how long I should stay. He explained details of subdural hematoma, the bouncing, the bruising, the bleeding of my brain. He told me that is why they pushed me aside after the CT scan because there was nothing they could have done. He said this is why they needed me to stay for six weeks of observation. I absolutely refused that. He suggested three.

“Tell you what, give me a business card. If any blood starts oozing out of my ears or anything, I’ll give you a call.”

“Why do you want to leave so badly? You don’t even know where you live.”

I pointed to a woman standing across the room.

“You said that’s my mother and I bet she knows where I live. Let me go.”

His expression became serious while he informed me that ninety-five percent of the people with a head injury such as mine die immediately.

“So, I’m the other five-percent. So, let me go.”

He shook his head.

“You don’t understand. The other five-percent are comatose until they die.”

We paused. He waited for me to understand the seriousness. I lingered. I was impressed. I understood his concern. I sympathized. It was just, I felt fine and I didn’t like restraint. Besides, they wouldn’t let me eat and I was starving. And I knew that when they did it wouldn’t be enough. I desperately wanted a big, sloppy hamburger and fried zucchini with ranch.

“Doc,” I leaned forward. “I gotta go.”

A mix of indignation and burden on his face. He slowly and deliberately approached me. He even more slowly and deliberately spoke.

“That you are sitting up in bed and speaking is medically impossible. I can’t explain it.”

I couldn’t either. His authority left me dumbstruck. I only had a sense, so said it.

“Sturdy peasant stock.

2005 Southern Illinois Writers’ Guild competition 2nd Place Essay.

Photo credit: Ranney Campbell, 2022

he slit me, sliced with scissors, the meat of me

the doctor decided this between my feet

without request, as was his privilege

when he saw you crown

not wanting to think women are built for it

to bend and curl around obstacles

and impositions like liquid

so you slipped through bloodied cut

into the stark room out of me and I would never be the same

was owned by you then

and then your father owned me too

and I told him

I had never known this feeling

didn’t know

it a thing possible

he smiled, believing

a new confidence in him, a father now, told me

if I ever tried

to leave him

he would take you

and I would never see you again

later, that you’d be better off dead

if I divorced him, threat meant

or that he had all the money

would hire psychologists to say I was crazy

secure custody

so, I stayed, of course, years

as he chipped away

but first at six weeks

the O B stuck his finger in me

said squeeze

gasped

wow your husband has nothing to worry about

he should be quite pleased good girl

Originally published by Rat’s Ass Review.

Photo: 1989.

Out of the corner her attention through and beyond the mud room to the patio carrying a laundry basket filled of fluffy squares on her hip paused when spotted the pretty girl, who three years earlier had slipped her vaginal canal and was whisked away covered in feces, such a delicate beaming, “Look mom. We’re painting. Like you,” long wooden handled camel hair in a fist like an icepick, scrubbing the hundred- and twenty-dollar fan brush it took ten weeks to save for a decade before, completing the collection, then to her son, he four, with another, sweeping it back and forth in a quarter inch of silt washed underneath the retaining wall as wet in a thunderstorm dried over weeks as there was no time yet to sweep, and her eyes went high to a shelf where she had stashed the cylindric tin she propped her brushes in since she was a teenager given to her by her grandmother that she thought she might take down again someday put there on the day she found the boy in acrylics and after she threw squished tubes away and spent hours cleaning colors from carpeting, but the tin was on its side and every other kind of her brushes lay frayed out there too and she had had violent thoughts in the past but nothing like the electrical chemical hormonal flood that day and in her head who are these people and why are they in my life screamed along with flashes of ripping their flawless arms off pummeling their perfect faces into red pulp so she pulled deep and closed her eyes and silently chanted instead I am not an artist. I am a mother. I am not an artist. I am a mother over and over until another kind of biochemistry came and when all the squares of neatly folded tiny clothes were tucked orderly into drawers folded up her easel and leaned it out of the way and called the city to find out when was the next big-trash-day.

Originally published by Pinyon , summer 2024.

Photo credit: Ranney Campbell, 2025.